The Secret Academy of Karlo Zvirynskyi

From 1959 to 1966, the artist Karlo Zvirynskyi ran an underground art school from his tiny apartment in Lviv. At a time when art was strictly controlled by the state, when the KGB could come knocking anytime, he gave his students a wonderful gift: freedom of thought.

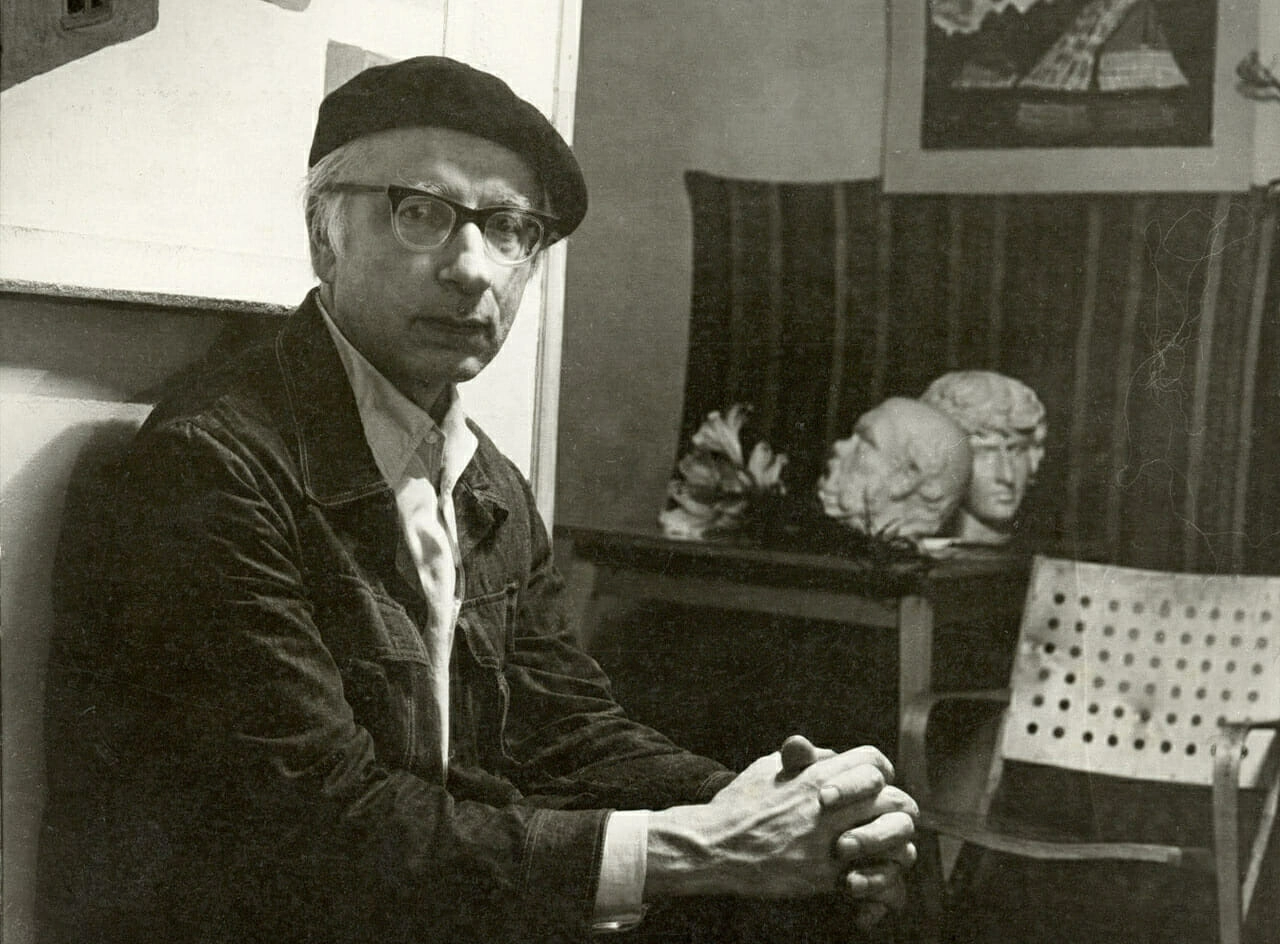

Karlo Zvirynskyi (1923 – 1997) was a painter and graphic artist who experimented with various forms and applications of art, even painting icons and churches. He also hated socialist realism with a passion. Later in life, in response to the bleak circumstances in which he lived, Zvirynskyi became a dedicated teacher, with a mission to teach his students something more valuable than “the terrible dogmatic laws that existed then in the institute”.

For eight years – from 1959 to 1966 – Zvirynskyi provided an underground education for the young artistic generation of the sixties, putting himself and his family at risk of imprisonment or death. His students included Zenovia Flint, Oleksandra Tsehelska, Oleg Minko, Andriy Bokotei, Roman Petruk, Bohdan Soyka, Stefania Shabatura, Petro Markovych, Ivan Marchuk, and Petro Hrytsyk.

Karlo Zvirynskyi was born in 1923 in the village of Lavriv, Lviv region. The family was poor when Karlo was growing up: he discovered life through the prism of books, as reading was almost his only form of entertainment. As a child, Karlo did not draw or paint much: he later recalled that the “bacillus of painting” awoke in him only at the age of 16, during an argument with his older brother over who could paint a better portrait of the Kobzar for the annual Taras Shevchenko days.

In 1942, Karlo got a place at the newly established Lviv State Art and Industrial School, having read about it in a newspaper ad. However, the war cut short his studies after only a year and a half. After graduating from Lviv Art School as a painter, Zvirynskyi considered returning to his village; instead, inspired by his teacher Roman Selskyi, he decided to continue his studies at Lviv Institute of Applied and Decorative Arts, in the department of monumental painting.

The young Karlo Zvirynskyi did not hide his nonconformist views: he was even expelled from the institute for a year for his refusal to accept socialist realism. “One apple of Cézanne is worth more than all the art of socialist realism combined,” he argued.

After graduating in 1953, he began teaching at the School of Applied Arts, and later at the institute. However, due to the continuing Soviet oppression, he had to take his teaching activities underground.

“I saw what students were taught. They were taught bad things, they were not taught what was necessary,” Zvirynskyi said. “If they went down that route, their talent would be lost, and they would also be lost as citizens. And so it seemed to me that I should do everything to help them preserve their natural talent and at the same time develop their human dignity, their civic awareness. I wanted them to know who they were, what they should do, and where to go.”

When Zvirynskyi first established the underground academy, his students would gather after sunset in the Zvirynskyi family home, in a room measuring 16 square metres. Meanwhile, to make space for the students, Karl’s wife would take their three children out for a long walk.

According to Zvirynskyi’s daughter Khrystyna, secrecy was paramount: if anyone found out about these gatherings, all the participants would be visited by the hebisty (KGB). To avoid being noticed, Karlo also often arranged meetings in different locations.

Khrystyna Zvirynska recalls the strict rules that were established to maintain the secrecy of the operation: if someone came by during a lesson, they would all pretend to be celebrating someone’s birthday. Students and friends would press the doorbell twice and then repeat. “If not, it meant that someone else was at the door. If Dad was at home painting icons, one of the children would go to the door, ask who it was, and tell them to come in later, because Dad wasn’t home,” explains Khrystyna. “When we got a phone, we knew it could be a listening device. If any of the students came, the phone was sandwiched between two pillows.”

Educating a young generation of artists took on the greatest meaning for Zvirynskyi: it was not just an education that he was providing; it was a kind of intellectual salvation. The artist noted that he ended up spending more time teaching than working on his own art: times were hard, and it could not have been otherwise. Thanks to his extraordinary erudition, he developed an entire educational program for his students, consisting not only of specialized art subjects but also general disciplines that contributed to the young artists’ intellectual development.

According to the art critic and researcher Bohdan Mysyuga, Zvirynskyi worked his students hard intellectually: “He gave them the names of books to read. Exupery, Schopenhauer, Camus… they read all the Nobel laureates: Beckett, Kafka, and so on.” Often the students would read in Polish, as Zvirynskyi was able to procure books via a colleague and brother in Poland. Later, the Zvirynskyis set up the Druzhba bookshop in their home, selling foreign books on art to a student clientele. Zvirynskyi also listened to BBC radio in Polish, where he was able to hear critical discussions on European art.

Zvirynskyi believed that it was impossible to study art without an awareness of related disciplines such as philosophy and music: he encouraged his students to look for relationships between styles in music and visual art. Many of his students were also talented musicians: “Bokotei led a student choir,” writes Bohdan Mysyuga. “Zvirynskyi himself played the mandolin, his student Soyka also learned to play the mandolin on the guitar.”

“All my painting is prayer,” said Zvirynskyi. You could say the same about his teaching: in a way, it was a radical act of faith, a prayer for openness and tolerance in the midst of narrow-mindedness and repression. A prayer for a better world.